Topaz from Mason County, Texas

Roy Bassoo, Diane Eames, Matthew F. Hardman, Kenneth Befus, and Ziyin Sun

Figure 1. A fine 925 ct crystal that was formerly displayed in the Texas State Capitol and sat on the governor’s desk in 1969 when the legislature adopted blue Texas topaz as the state gem. This specimen was found in 1904 and now resides in the Hamman Gem and Mineral Gallery in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at the University of Texas at Austin (catalog no. B0344). Photo by Blanca Espinoza.

METHODS

RESULTS

CONCLUSIONS

Figure 1. A fine 925 ct crystal that was formerly displayed in the Texas State Capitol and sat on the governor’s desk in 1969 when the legislature adopted blue Texas topaz as the state gem. This specimen was found in 1904 and now resides in the Hamman Gem and Mineral Gallery in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at the University of Texas at Austin (catalog no. B0344). Photo by Blanca Espinoza.

Figure 1. A fine 925 ct crystal that was formerly displayed in the Texas State Capitol and sat on the governor’s desk in 1969 when the legislature adopted blue Texas topaz as the state gem. This specimen was found in 1904 and now resides in the Hamman Gem and Mineral Gallery in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at the University of Texas at Austin (catalog no. B0344). Photo by Blanca Espinoza.

ABSTRACT

Gem-quality naturally blue topaz occurs in Mason County, Texas. Known as “Texas topaz,” this gem is highly sought after in the United States because of its domestic provenance and rare natural blue color. To date, no studies have identified gemological or compositional characteristics that could distinguish Texas topaz from topaz sourced elsewhere. This study provides a historical account of topaz from Mason County and discusses its geologic origin, compositional characteristics, manufacture, and significance to the gem trade. A total of 83 alluvial topaz crystals from Mason County were analyzed using standard gemological testing; Fourier-transform infrared, ultraviolet/visible/near-infrared, and Raman spectroscopic techniques; and laser ablation–inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry to gather gemological and geochemical data. Most Texas topaz is colorless, though some is light blue or brown. A small percentage of the blue stones displayed a saturated bodycolor. Color zoning was often visible and became more noticeable with luminescent excitation. Ultraviolet luminescence at 225 nm excitation revealed green to blue luminescent growth bands and rarely red luminescent growth bands. Topaz crystals from Mason County are not often free of inclusions. When present, multiphase melt and fluid inclusions contain carbon dioxide. Mineral inclusions include albite, anorthite, quartz, muscovite, pseudobrookite, and columbite-tantalite. Machine learning algorithms were applied to fingerprint the trace element composition of the samples. Trace concentrations of phosphorus, scandium, titanium, iron, gallium, germanium, niobium, tin, tantalum, and tungsten best constrained the formation and provenance of Texas topaz. For gemologists, these trace elements can also aid in assessing the geographic provenance because most Texas topaz presents a distinct trace element composition. This work demonstrates the potential effectiveness of machine learning and statistical modeling in gemstone provenance determination. These can be powerful tools in conjunction with traditional gemological discrimination techniques.

"Topaz is an orthorhombic nesosilicate with the general chemical formula Al2SiO4F2. It can form from fluorine- and lithium-rich, peraluminous (aluminum-rich and calcium-poor), and highly fractionated silicic melts or gases geologically associated with rhyolites, pegmatites, or hydrothermal-greisen rocks (Burt et al., 1982; Congdon and Nash, 1988; Payette and Martin, 1990; Menzies, 1995; Zhang et al., 2002; Marshall and Walton, 2007; Gauzzi et al., 2018; Gauzzi and Graça, 2018). In pegmatites, topaz is found alongside quartz, feldspar, muscovite, and accessory tourmaline and fluorite (Pollard et al., 1989). In greisens, which are granitic rocks altered by internal magmatic fluids, topaz is also associated with rare metal deposits of tantalum, niobium, tungsten, lithium, tin, and molybdenum (Burt et al., 1982; Manning and Hill, 1990; Taylor, 1992; Raimbault et al., 1995; Charoy and Noronha, 1996; Williams-Jones et al., 2000).

Globally sourced gem and fine mineral specimens of topaz are prized for their luster, clarity, hardness, and wide range of colors, including orange, pink, and blue. Whereas most topaz is colorless, certain growth environments induce defects and impurities that create color centers. In the case of pink to violet colors, Cr3+ acts as a chromophore, substituting for Al3+. A combination of oxygen-to-metal charge transfer and radiation-induced color centers can modify pink to violet material to orange Imperial topaz (Gaft et al., 2003; Schott et al., 2003; Taran et al., 2003). Oxygen hole center defects produce brown or blue colors, though the possibility of additional defects causing blue color remains uncertain (Krambrock et al., 2007; Rossman, 2011). Pronounced blue colors can also be created or enhanced through irradiation and heat treatments (Simmons, 2007). Colorless topaz was first irradiated to create a blue color in 1957 (Pough, 1957). Artificially irradiated and heat treated blue topaz subsequently entered the market in the late 1970s, and its popularity and low cost eventually made it the most commonly irradiated gemstone on the market (Nassau and Prescott, 1975; Crowningshield, 1981; Nassau, 1985). This treatment became so widespread that any blue topaz in today’s market is assumed to have been irradiated (Rossman, 2011).

Figure 2. Rough topaz from Mason County analyzed in this study, showing the range of color of this material. The large blue specimen weighs 188 ct. Photo by Emily Lane; courtesy of Diane Eames.

Considering the prevalence of artificially blue topaz, the naturally blue topaz from Mason County, Texas, is significant (figure 1). Indeed, faceters of Texas topaz understand that treating this gemstone could render it indistinguishable from those found in other locations. In Mason County, as with most geographic occurrences, colorless topaz is the most common. However, faint blue to sky blue hues can be relatively uncommon. Pink, brown, and gray colors are rare (figure 2).

Topaz was first collected in Mason County in the late 1800s, long before the first reported accounts of topaz treatment (Meyer, 1913; Leiper, 1951). By the 1950s, Texas topaz had become important in the regional gem trade (White, 1960; Towner, 1968, 1969; Browne, 1982). The timing is anecdotally linked to World War II, when scientists moved to the American Southwest for the nuclear weapons program and engaged in recreational mineral hunting on weekends and holidays. This led to the formation of gem and mineral groups and increased rockhounding and gem faceting in the region. Topaz from Mason County became the most commonly used gemstone in faceting competitions at Texas gem and mineral shows. In 1969, the state legislature adopted Mason County blue topaz as the official state gemstone, introducing the “Texas topaz” label.

Figure 3. Faceted Texas topaz specimens with brown, blue, and green bodycolors, ranging from 0.62 to 9.34 ct. Texas topaz has been sought after for its naturally occurring blue color. Photo by Brad Hodges; courtesy of Diane Eames.

Texas topaz remained in the hobbyist realm until the early 2000s, when Diane Eames and Brad Hodges established Gems of the Hill Country, a jewelry store in the town of Mason. From this rural platform they built a successful niche jewelry business centered on locally sourced and manufactured Texas topaz pieces (figure 3). Gems of the Hill Country supplied both local and national markets with jewelry showcasing Texas topaz. Their advertising campaign significantly elevated the prestige of Texas’s state gemstone.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

BOX A: CUTTING OF TEXAS TOPAZ

Topaz is popular with American faceters for its perfect basal cleavage plane. To prevent breakage during faceting and scratches during polishing, a gem cutter must avoid placing the table along the cleavage plane. Chips along the girdle may indicate that the cleavage plane is parallel to the girdle, which is also undesirable. The strongest color saturation in topaz occurs parallel to the c-axis. Therefore, faceters cannot simply orient the stone away from potential weakness associated with the basal cleavage without sacrificing color. To optimize color and avoid structural weakness, faceters attempt to cut topaz so that the table is ~7° off the cleavage plane, an orientation that minimizes fractures and accentuates color. A Texas topaz faceted with a 0.5 micron polish and a correctly oriented cleavage plane can achieve subadamantine luster and deeply saturated color, both of which contribute to its appeal.

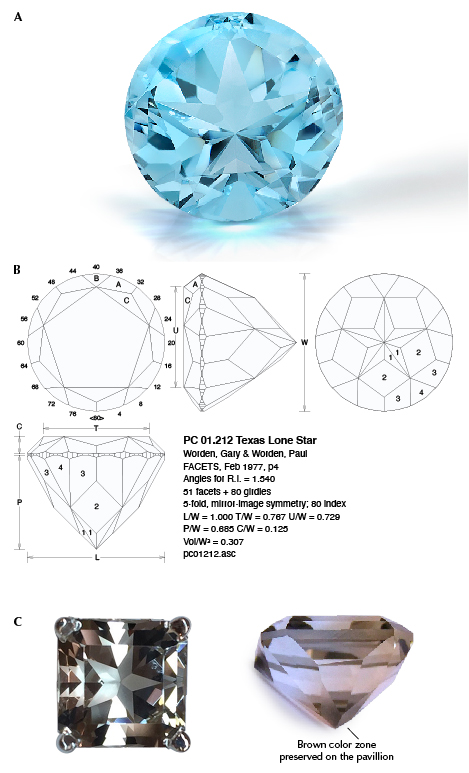

Figure A-1. A: 14.5 mm round 13.8 ct topaz from Mason County, Texas. Photo by Blanca Espinoza; courtesy of Form to Feeling. B: Facet design for Lone Star cut (from the open database at http://www.facetdiagrams.org). C: A cut topaz with brown color zones deliberately positioned along the pavilion to display a brownish bodycolor in the table view. Photos by Brad Hodges.

The development of the Lone Star cut (figure A-1, A) distinguished Texas topaz as a regionally unique and desirable gemstone. The facets on its pavilion produce a large five-point star visible through the table, a shape reminiscent of the star in the Texas state flag. The pavilion of the traditional Lone Star cut represents up to 80% of the stone’s total depth, making it unsuitable for rings and earrings. Alternative versions have a pavilion that accounts for 60–65% of the total depth, and these have become popular. Most are cut as round gems, but fancy Lone Star variations have also been developed.

Several Texas faceters have contributed to the design and popularity of the Lone Star cut. Gary Worden and Paul Worden of San Angelo are credited as the original designers (Worden, 1977; see figure A-1, B). Additional star cuts were developed by hobbyist faceters. The most influential were Charles Covill and Robert Strickland, both of Austin, who developed many variations and freely shared their designs with other gem cutters.

The commercial development of Lone Star cut Texas topaz initially relied on independent hobby cutters mainly selling their work in the town of Mason. With the opening of the retail store Gems of the Hill Country in 2007, manufacturing shifted to a commercial scale. Cofounders Diane Eames and Brad Hodges sourced, faceted, and designed Texas topaz jewelry pieces, providing a retail avenue for the state gem. Acquiring topaz from local rock hounds, ranchers, and topaz enthusiasts, Gems of the Hill Country expanded its inventory of gem-quality blue, pink, and brown topaz (figure A-1, C). Gems of the Hill Country has since closed, but the founders still maintain a large inventory of Texas topaz. During its decade-plus run, Gems of the Hill Country not only sold Texas topaz to buyers in the United States, Germany, and the United Kingdom but also founded and participated in Texas Topaz Day in Mason from 2008 to 2012, celebrating Texas topaz with a public mineral hunt on local topaz-bearing ranches. These efforts elevated the awareness and prestige of Texas topaz and “American-made” gemstones and jewelry.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Because of its local provenance, topaz from Texas has a much higher regional value than similarly colored topaz from other localities worldwide. The most sought-after stones exhibit a saturated blue color. Price varies with the saturation of blue color and the cut quality. Early in the twentieth century, faceters used the Portuguese cut to create stones with deep pavilions to intensify the pale colors. Today most of this topaz is faceted in the Lone Star cut (box A) or variations thereof. Blue or brown color zones are placed in the culet to intensify the perceived color (King Jr., 1961).

Establishing the provenance of Texas topaz has posed a challenge in the regional gem trade. Buyers are wary of intentional or inadvertent substitution of low-value foreign topaz for high-value local material. This article presents a gemological and analytical study of Texas topaz to augment the various worldwide databases of colored stone deposits. Trace element compositions for topaz from Mason County are presented, along with a demonstration of how machine learning can assist with the geographic provenance determination of Texas topaz.

GEOLOGY AND MINING

MATERIALS AND METHODS

RESULTS

CONCLUSIONS... "

https://www.gia.edu/gems-gemology/winte ... exas-topaz