To top it off, Fairtrade America and Fairtrade Canada charge over $2,000 in fees for the use of the Fairtrade seal/logo, which is otherwise free for jewelers elsewhere around the world. Does anyone else see something wrong with this picture, or is it just me?

A dream deferred: Ethical gold in North America

May 28, 2020

By Marc Choyt

Photo courtesy Marc Choyt/Reflective Jewelry

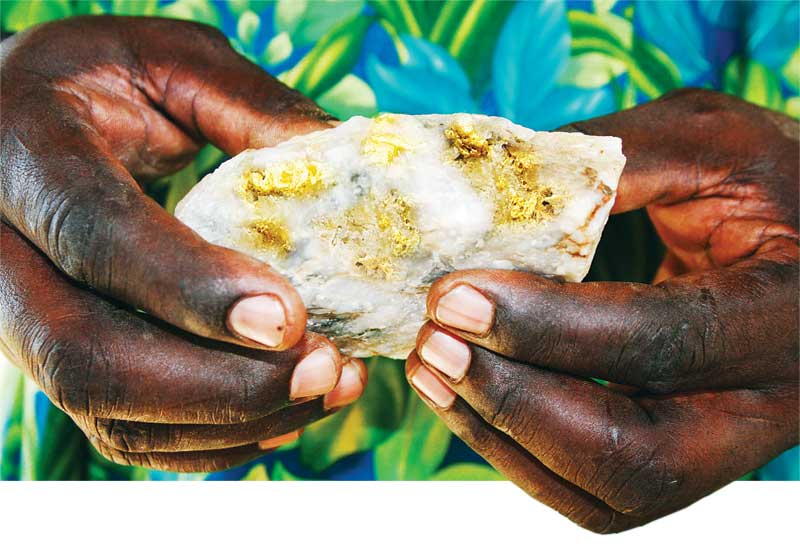

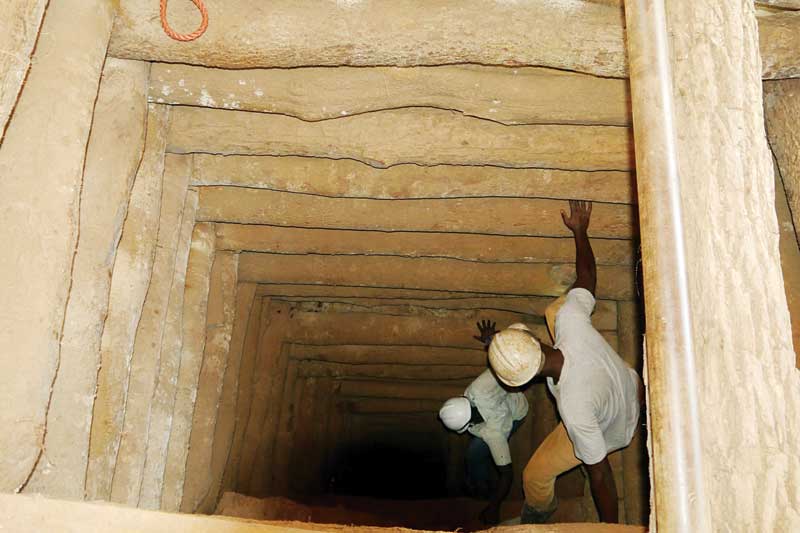

"Beneath the green skin of Tanzanian farmland, two men dig for gold. I can hear their picks strike the hard earth 20 yards down a six-by-six foot, log-reinforced vertical tunnel.

I had travelled forty hours from my Santa Fe, N.M., home to visit a gold mine, which was attempting to achieve certification from Fairtrade International. Even reaching proximity to these strict international protocols was an achievement—not only is the required documentation extensive, but the foundation’s on-the-ground standards would mean big changes for the small-scale miners.

After all, why use a retort that collects mercury when it can, instead, just be poured into a river? And why shouldn’t children, especially orphans who had lost parents in mining accidents and need the means to survive, be put to work, especially when attending school is unaffordable?

This was autumn 2014. I had been selling my own designs, made with fairtrade gold, since 2011; the following April, I would go on to become the first fairtrade gold-certified jeweller in the United States.

On this day, in Tanzania, through the generators’ blue/grey diesel smoke, I could just make out the miners’ headlamps.

That fragile light, I thought, would one day ignite a movement in the jewellery world as radiant as the sunrise over the green savanna. This mine, already attracting regional attention, would be the seed that would uplift other African miners—giving them access to international pricing and North American consumers, passionate about being part of the solution.

A market failure

Small-scale miner in Peru panning for ‘green gold.’ This technique involves no use of chemicals and minimal damage to the environment.

Photo by Greg Valerio

Six years later, it’s obvious the North American market for gold from fairtrade- and fairmined-certified small-scale mines has failed to gain any traction.

Back home in Santa Fe, I remain the only fairtrade gold jeweller in the U.S.—likewise, only one exists in all of Canada. Fairmined gold, which carries similar standards to fairtrade, is used by a few more studios, but has had no significant market impact.

Understanding why this is the case is complex—indeed, it’s akin to opening the various layers of a Russian Matryoshka doll. But it begins with photos and stories told to the press and to customers about responsible gold.

Narratives are what influence and, by extension, ultimately determine the market.

Leading with small scale

When unpacking this, a good place to start is the lead photo for the 10th Annual International Gold Conference.

Attendees of the conference are an A-list of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), consultants, retailers, and manufacturers—among them are key representatives of the Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC), such as De Beers Group and Richline.

The event’s lead photo depicts a small-scale miner, panning for gold. Not just any gold, but alluvial gold—perhaps the least harmful gold mining activity, with no mercury needed.

Using images of small-scale miners has been a key strategy for multinational initiatives for years. Between 2013 and 2018, for example, RJC’s website featured photos of small-scale miners prominently in three of its eight homepage images.

Small-scale mining, particularly in regard to the gold and diamond sectors, is the part of the jewellery supply chain that is the most vulnerable to criticism. Indeed, these gold miners who dig with shovels are widely exploited; they work in terrible conditions and are the largest contributors of global mercury pollution.

These photos and their corresponding agendas demonstrate to the world the ways in which the jewellery trade is concerned about these injustices, but not without irony. At least through 2019, the total amount of ethical, small-scale gold produced and sold annually likely equates to less than retailers attending the conference sell in a few days. Note there are no small-scale miners keynoting this conference.

Perhaps most revealing is this: if this issue is of global concern, why don’t the eminent, national brands use fairtrade gold to make their jewellery? Such a move would ignite a powerful, consumer-driven market that could, over time, alleviate poverty and reduce global mercury contamination.

Indeed, this market proposition has already been proven!

A fork in the road

In the United Kingdom, where there are more than 250 registered Fairtrade Gold jewellers, trade publication Professional Jeweller named Fairtrade Gold a major market trend in 2017. As such, Fairtrade Gold jewellers are able to take advantage of the powerful Fairtrade brand and logo. In the U.K., studies have shown nine in 10 consumers recognize the logo and believe it aligns with personal values.

Throughout 2019, major suppliers in the U.K., such as Hockley Mint, provided a full line of fairtrade gold bridal and mill products. Indeed, fairtrade gold has been the foundation of the U.K.’s ethical jewellery movement, bridging the gap between the sourcing and the symbolism of a wedding ring.

A small-scale mine in Tanzania, aiming to achieve Fairtrade Gold certification.

Photo by Marc Choyt

In the U.S., however, recycled gold is the foundation of ethical jewellers—a narrative that began in 2007 and was pioneered by Hoover and Strong’s ‘Harmony’ line.

Though jewellers have been recycling metal forever, recycled gold provided an acceptable response to Oxfam and Earthwork’s ‘No Dirty Gold’ campaign, which started in 2004.

I was an early adopter and advocate of recycled gold, because it at least raised the profile of ethical sourcing concerns, but perhaps the most powerful supporter was Brilliant Earth. More than any other company, this brand drove the recycled gold story—even claiming, “choosing recycled gold… decreases the global demand for newly mined gold.”

… Really? Everyone knows gold is a currency hedge.

Small-scale miners, who produce 20 per cent of the world’s gold while simultaneously making up 90 per cent of the world’s gold mining labour, will continue to dig in the earth. Whether gold is valued at $500 or $1800, they mine to feed themselves and their family.

Meanwhile, for large-scale companies, well represented at the Gold conference, mining depends on gold price, concentration of ore in rock, and the degree of difficulty to extract.

Yet the American industry has coalesced around ‘eco-friendly’ recycled gold. Stuller and Rio Grande have equated recycled precious metals as the sustainable choice—and why not?

Recycled gold requires little adjustment to the supply chain, and has a great halo effect to consumers who think the metal is analogous to recycled paper or aluminum—it doesn’t matter to them that it’s just dirty gold, rebranded as ‘green’ after it goes through a refinery.

Regardless, recycled gold is significantly cheaper than fairtrade or fairmined gold.

The cost problem

Though the all-pervasive ‘eco-friendly’ recycled gold story is, perhaps, the biggest obstacle to a supply chain based on support to producer communities, cost is also a huge deterrent.

Back in 2012, Fairtrade flew me to London to meet with key jewellers, as well as miners, major supply houses, and company officials. At the time, the Fairtrade premium—what the miners were set to receive on top of their international price—was linked to the gold spot price.

The jewellers wanted less cost; the miners wanted more. The final number of US$2000 per kilo (about a four per cent upcharge) would allow the cost of an average wedding ring to be about $30 more—a number that U.K. consumers might accept.

Fairtrade meeting in London, October 2013.

Photo by Marc Choyt

Over the past eight years, Alan Frampton, CEO of CRED Jewellery, supplied fairtrade gold to supply houses at plus five per cent and, to a few small studios, at plus eight per cent over spot. Exporting gold from small-scale mines is generally a huge logistical nightmare, which Frampton had solved by visiting mining sights dozens of times and developing relationships with the miners.

He was the keystone to the global fairtrade movement; however, this past year, RJC member Valcambi bought exclusive rights to the mine of Frampton’s main source. CRED went out of business.

Hoover and Strong still supplies the American market with Fairmined and Fairtrade gold—but the cost, with fees, approaches 20 per cent over spot.

And it’s not just the cost of metal. To make rings, I alloy 24-karat and roll it into sheet and wire. Small amounts of 14-karat white, yellow, and rose gold that get left over from small casting runs eat cash flow. It’s totally unscalable.

A two millimetre wedding band might be relatively inexpensive to produce in fairtrade gold, even if we have to start with 24-karat casting grain, but $200 will not cover additional costs for a thicker band, a custom cast project, or a design that has a lot of labour.

Forget wholesale—and forget the possibility of more studios joining to create a movement in North America.

While Fairtrade organizations around the world have a free entry scheme that allows jewellers to access global branding and use the logo in their marketing, Fairtrade America charges more than $2000 in fees for use of its stamp, and Fairtrade Canada has a similar pricing scheme. Further, Fairtrade UK strongly promotes fairtrade gold, while the material is seldom (if ever) promoted by Fairtrade America.

The triumph of responsible gold

For now, the future of ethical gold in North America is rooted in recycled and ‘responsible’ gold from the RJC.

The foundation of this new responsibility for large-scale mining is 1) traceability; and 2) transparency (for more on this, see “What makes ethical jewellery ethical?” in the August 2018 edition of Jewellery Business).

This is not so difficult, really; after all, if you own a mine and control its chain of custody, achieving this level of responsibility is merely certifying what you already have. As Michael Ray, a former chief executive officer of RJC, once revealed in an interview I published, the council is “in essence, a trade association.”

The conflict of interest between being a trade association and certification agency has not, as of yet, been much of a concern to jewellers.

However, in a 2018 critique of the RJC, Human Rights Watch (HRW) noted agencies, such as consumer groups, unions, and miners’ associations, have been excluded from decision-making bodies. Additionally, the group wrote, “The Responsible Jewellery Council promotes standards that allow companies to be certified even when they fail to support basic human rights.”

A gold bar from MACDESA, a Fairtrade-certified mining company in Peru.

Photo by Alan Frampton

Despite these observations, NGO critiques have, somehow, ignored an issue that is perhaps even more pervasive and significant: the RJC ‘grandfather clause.’

As of January 2012, all existing materials were grandfathered into the current RJC ‘responsible gold’ standard. As such, regardless of current practices, AngloGold Ashanti, BHP Billiton, Newmont, and Rio Tinto are certified as producing ‘responsible gold’ despite human rights and environmental atrocities documented by the London Mining Network and others.

What if, for example, the Pope declared child abuse committed by priests before 2012 was now forgiven? Such a statement would be preposterous and unheard of—yet, somehow, in the ethical jewellery scheme of our industry, erasing history is critical to establishing new standards.

A similar approach was taken during the formation of Kimberley Process (KP) Certification in 2002. Approximately 3.7 million people have died in wars funded by diamonds, yet no one in the jewellery sector has ever been held accountable.

Perhaps this is a contributing factor as to why KP Certification, now 17 years old, is so ineffective—or, in the words of Martin Rapaport, ‘bullsh*t.’

I have little doubt that if the international community had required accountability, truth, reconciliation, and restitution to impacted communities, we would have a more authentic ethical jewellery movement by now.

Market control

For nearly 15 years, I’ve been a pioneer in the ethical jewellery movement; I have watched and attempted (as best I can) to steer benefit toward the small-scale producer.

In 2006, when I attended the JCK Show in the Designer Pavilion, I talked to other store owners about fairtrade gold. There was zero interest.

These days, ethical jewellery is not just a trend; it is at the heart of marketing for Gen-Z and millennial shoppers—nonetheless, it seems the high-profile photos and small initiatives for miners hide as much as they reveal.

To quote the great Leonard Cohen, “Everybody knows the fight was fixed / The poor stay poor, the rich get rich.”

With the exception of the disruptive impact of lab-grown diamonds, when we look at the impact on the mainstream market, there have been no significant changes in recent years in how jewellery materials are sourced in North America.

Returning to the 10th Annual International Gold Conference: the event’s invitation includes the same ‘all that glitters’ branding that was used to introduce fairtrade gold to the U.K. in 2011. The invite also encourages industry members to ‘embrace mindfulness of sustainability and of our obligations to the planet.’

Unfortunately, this embrace does not include meaningful support of the miner who, today, might burn off their mercury amalgam in ... "

https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/featu ... nt=feature